The current conversation on mission command among some professional circles is on the brink of becoming unhealthy, even dangerous to the military profession as a whole. Heavily-biased dialogue, when left unchecked by critical thinking, can quickly become divisive no matter how well-intentioned. In his chapter, "The Sinews of Leadership: Mission Command Requires a Culture of Cohesion," recently published in an anthology on mission command entitled Mission Command: The Who, What, Where, When, and Why, author Joe Labarbera asserts that the Army's fighting forces lack the cohesion necessary to survive on the modern battlefield. He cites a culture of careerism and a turbulent personnel management system among numerous other factors as sources of the problem. While his ideas might contain truth, his work serves as an example of recent dialogue on the topic that possesses the potential to do more harm than good. Deeply-biased and dredging up feelings of discontent and frustration, his work is less likely to aid in identifying potential solutions than it is to drown them out.

Labarbera places much of the blame for alleged low levels of cohesion within the ranks on a culture of careerism, wherein leaders demonstrate more commitment to advancing their own careers than developing teams and readying their formations for combat. Junior leaders and Soldiers, upon seeing their leaders' commitment to climbing the ranks as opposed to improving the organization, lose faith in their leadership and the organization as a whole. The author argues that the Army's officer evaluation system, so heavily dependent on the perceptions of one's rater and senior rater, promotes a climate wherein compliance and aversion to risk have become the norm. The result, in Labarbera's words, is "no shortage of popinjays who pontificate about leadership, while they cozy up to their next top block, making clever presentations that sell illusions of success and prostituting themselves to their rater's image of success."

Here, the author's bias bleeds through. Labarbera offers the reader a false dichotomy, wherein Army officers either seek to appease their chain-of-command or achieve meaningful results in their organization - they cannot do both. The reader must blindly accept the author's cynical notion that our organizational leaders' goals are completely uncoupled from accomplishment of the organization's mission. Undoubtedly, there are leaders for which this is unfortunately the case. Indeed, many readers have likely encountered one such leader during their career. However, Labarbera offers no real evidence to support his claim that this is common throughout the US Army. Such evidence, if provided, could persuade more critically-minded readers that this problem is the rule rather than the exception. Without it, the message only seems to cater to those readers who have likely already concluded that a culture of careerism exists.

Labarbera also asserts that the lack of longevity in individual Soldiers' assignments to a particular formation contributes to low levels of cohesion. When personnel are constantly flowing into and out of the ranks of a unit, the bonds of trust between Soldiers, and thus the cohesion of the unit as a whole, must be constantly reforged. Tactics, techniques, and procedures, as well as standard operating procedures, seem to change with every transition in leadership. Collective proficiency at echelon is hard-won through tough, realistic training and easily lost with each wave of the manning cycle. The cost of this phenomenon is a perpetually depressed level of readiness. As with his other assertions, data to support this claim would prove valuable to convincing readers of the scale of this problem. Further research and data to support this claim would likely prove enlightening to all readers.

Yet, the author casually dismisses the need for such statistics, stating "This is an obvious truth, yet many officers reading this will deny it if a statistic isn't cited. As an institution, the Army has lost it's ability to see reality and only sees malleable data as indicative of situational awareness." This idea - that detailed analysis is anathema to mission command - seems a pervasive sentiment in current professional dialogue taking place on social media. It is unhealthy and dangerous to the profession. To dismiss intellectual rigor and perseverance is to threaten the underpinnings of critical thinking, an essential element of advancing the profession. If decision-makers capable of addressing the problem are Mr. Labarbera's intended audience, reasoning based on emotion rather than data is unlikely to move them to action. But those more susceptible to his approach, such as inexperienced and impressionable Soldiers and officers or those lacking a critical mind, might begin to adopt his divisive biases as their own. These biases, unchecked by critical thought, have the potential to breed cynics and discontents. Where intellectual rigor, humility, and empathy are lacking, opposing sides draw battle lines, entrench, and engage in meaningless partisan conflict. In the end, few win and the profession advances little.

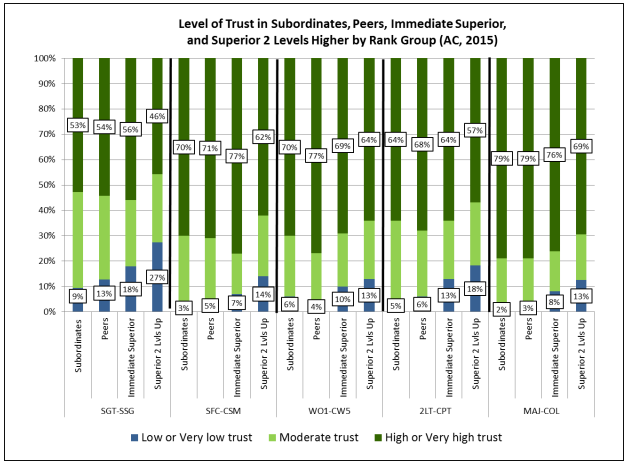

Data collected on unit cohesion and the impacts of careerism and turbulent manning cycles presents a mixed picture. Consider the results of 2015 Center for Army Leadership’s Annual Survey of Army Leadership (CASAL), wherein 83% of Soldiers surveyed report that a favorable level of trust exists between members of their unit or organization. On an individual level, over two-thirds of Soldiers express high levels of trust in their superiors, peers, and subordinates (Figure 1). Perhaps the situation with respect to cohesion within formations across the Army is not as dire as Mr. Labarbera believes. Yet, it is true that bad leadership exists and has a negative impact on the force. Indeed, a 2011 Center for Army Leadership (CAL) report on toxic leadership estimates that nearly one in five Army leaders are viewed negatively. Many of these are toxic leaders, who CAL defines as those who “work to promote themselves at the expense of their subordinates, and usually do so without considering long-term ramifications to their subordinates, their unit, and the Army profession.” The impact that these toxic leaders can have on a formation can be immense and Mr. Labarbera is correct in demonstrating his concern on their potential impact. Analysis of additional evidence presented in these studies would go a long way to better inform the audience of the prevalence and impact of these problems.

2015 Center for Army Leadership Annual Survey's findings on levels of trust between US Army Soldiers indicates that a significant majority of Soldiers report trusting their superiors, peers, and subordinates, though to a lesser extent when asked about superiors two levels up.

Critical thinking and communication is hard, deliberate work. It requires humility, open-mindedness, rigor, and courage. This blog has often struggled, and sometimes failed, to get it right. My own preference for (or bias towards) analytical rather than pejorative thinking and communication is painfully apparent in this writing. And yet, I believe it is a goal worth pursuing for all professionals. Critical thinking and communication facilitate shared understanding, with which we can begin to tackle even the profession's most daunting challenges.

The Army needs a well-informed, well-reasoned, rational discussion of the issues impacting our Army's ability to embody the mission command philosophy. "The Sinews of Leadership: Mission Command Requires a Culture of Cohesion” does not fill this need. Mr. Labarbera accuses the institution of suffering from cultures of careerism, politics, micro-management, and compliance. The author is clearly passionate about the mission command and demonstrates a clear, well-intentioned concern for its success in the US Army. Assertions by such professionals are disconcerting and should demand our attention. Yet, he falls short by offering no real evidence to support his claims. Nor does he articulate the impact of these maladies in a meaningful way. Throughout the course of the article, he raises pressing questions for the professional warfighter to consider: What are the effects of our evaluation system on organizational culture? What measures of performance and effectiveness should we employ to manage talent across the Army? To what extent does our current personnel management system negatively contribute to unit readiness? Unfortunately, any urge to think critically about these issues is drowned beneath a sea of bias and appeals to emotion, namely discontent and frustration. And therein lies the tragedy, because critical and thoughtful dialogue between military professionals on these issues is very much worth having.

No comments:

Post a Comment